Scaling an Online Virtual World with Serverless Tech

I help run an annual game design conference called Roguelike Celebration. Naturally, this year we were a virtual event instead of in-person for the first time. However, instead of just broadcasting a Twitch stream and setting up a Discord or Slack instance, we built our own custom browser-based text-based social space, inspired by online games and MMOs!

I’ve written about the design underlying our social space, as well as our approach to AV infrastructure, but in this article I wanted to talk about the technical architecture and how we used serverless technology to design for scale.

From an engineering standpoint, we built an open-source real-time game and chat platform. We eventually ended up selling around 800 tickets, meaning we needed to support at least that many concurrent users in a single shared digital space.

Our timeline for the project was incredibly short — I built the platform in about three months of part-time work aided by a handful of incredibly talented volunteers — which meant we didn’t really have time to solve hard scaling problems. So what did we do?

Overall Server Architecture

A “traditional” approach to building something like this would likely involve building a server that could communicate with game clients — likely a combination of HTTP and WebSockets, in the case of a browser-based experience — as well as read/write access to some sort of database.

If we ended up having more concurrent users than that one server could handle, I’d have two options: run the server process on a beefier computer (“vertical” scaling) or figure out how to span multiple servers and load-balance between them (“horizontal” scaling).

However, on such a tight time scale, I didn’t want to get into a situation where I would need to design and run load tests to figure out what my needs and options were. It’s possible none of these scaling issues would actually be relevant given the size of our conference, but it wasn’t possible to be confident about that without investing time we didn’t have into testing. Particularly, I knew from experience that scaling WebSockets is an especially frustrating challenge.

Instead, I reached for a “serverless” solution. Instead of provisioning a specific server (or set of servers), I would use a set of services that themselves know how to auto-scale without any input on my end, charging directly for usage.

This sort of architecture often has a reputation for being more expensive than just renting raw servers (more on costs later!), but in our case it was well worth the peace of mind of not having to think about scaling at all.

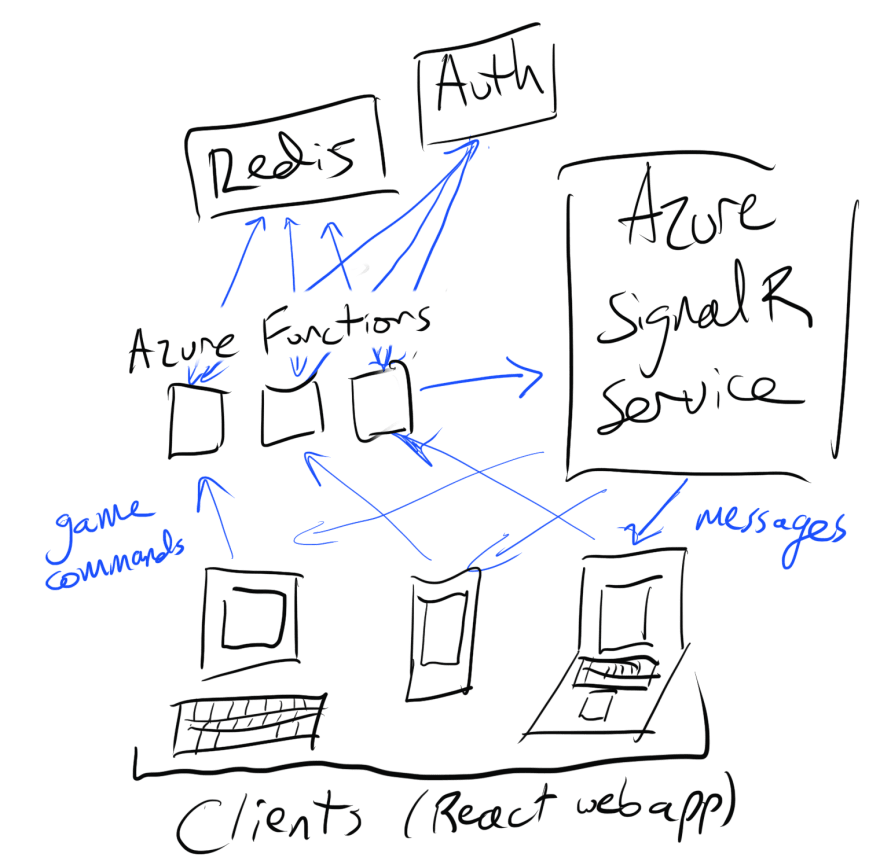

Here’s a high-level look at the architecture we ended up building:

If I wanted to not have to think about scaling, we needed our server-side code to be running on a serverless platform such as Azure Functions. Instead of deploying a proper Node.js server (our code was all written in TypeScript), I wanted to be able to upload individual TypeScript functions to be mapped to specific HTTP endpoints, with our cloud provider automatically calling those functions as needed and automatically scaling up capacity as needed.

However, as a real-time game, we also needed real-time communication. The typical way to do this in a web browser is to use WebSockets, which require long-standing persistent connections. That model isn’t compatible with the serverless function model, where by definition your computing resources are fleeting and each new HTTP request is processed by a different short-lived VM.

Azure SignalR Service

Enter Azure SignalR Service, a hosted SignalR implementation designed to solve this problem. If you’re familiar with WebSockets but not SignalR, you can think of SignalR as a protocol layer on top of WebSockets that adds features like more robust authentication. But for our purposes, what matters isn’t the use of SignalR instead of raw WebSockets, but the fact that Azure SignalR Service is a hosted service that can manage those long-standing connections and provide an API to communicate with them from short-lived Azure Functions code.

The only issue is that Azure SignalR Service only handles one-way communication: you can send messages to connected clients from the server (including our serverless functions), but clients can’t send messages back to the server. This is a limitation of Azure SignalR Service, not SignalR as a protocol.

For our purposes, this was fine: we built a system where clients sent messages to the server (such as chat messages, or commands to perform actions) via HTTP requests, and received messages from the server (such as those chat messages sent by other clients) over SignalR. This approach also let us lean heavily on SignalR’s group management tools, which simplified logic around things like sending chat messages to people in specific chat rooms.

HTTP requests and latency

Using HTTP requests for client-to-server messages did add extra latency to the system that wouldn’t exist if we could do everything over WebSockets instead. Even using WebSockets by itself can be a performance issue for particularly twitch-heavy games, as being a TCP-based protocol often makes speedy packet delivery trickier than the UDP-based socket solutions most fast-paced multiplayer games use.

These are problems that any browser-based game needs to solve, but fortunately for us, we weren’t dealing with 2D or 3D graphics and a networked physics model and other systems that typically complicate games netcode. As a text-based experience, the extra tens to hundreds of milliseconds of latency added by using HTTP requests for client-to-server messages were totally acceptable.

Redis as a persistence layer

From there, we also had a persistence layer to handle things such as remembering players’ user profiles and who was in what room (we didn’t store text messages, other than dumping them to a controlled audit log only accessed when addressing Code of Conduct violations).

We used Redis, a key-value store primarily intended to be used as a caching layer. It worked great for our purposes: its ease of use made it easy to integrate, and its emphasis on speed helped make sure that database access didn’t add to latency, since we were already incurring extra latency from our reliance on HTTP requests. Redis sometimes isn’t as suitable for long-term persistence compared to a proper database, but given we were running an ephemeral installation for two days that didn’t matter.

That said, any sort of database or key-value store would likely have worked great for our admittedly simple needs.

So… did it work?

We were easily able to support hundreds of concurrent users in the same space during our live event, and had absolutely zero issues with server performance or load. Azure Functions can scale more or less infinitely, Azure SignalR Service gave us a clear path to upgrade to support more concurrent users if we needed to (up to 100,000 concurrents), and our Redis instance never went above a few hundred kilobytes of storage or above 1% of our available processing power, even using the cheapest instance Azure offers.

Most importantly, I didn’t need to think about scale. The space cost about $2.50 per day to run (for up to 1,000 concurrent users), which might have been prohibitively expensive for a long-lasting space run as a non-profit community event, but was absolutely fine for a time-bounded two-day installation (and I’m already working on ways to bring that cost down).

I’ve used this general architecture before for a previous art installation, but seeing it work so flawlessly with a much larger conference gave me confidence it would have scaled up to even 10x as many attendees without any trouble.

Design your way around hard problems instead of solving them

In general, I’m really optimistic about this sort of serverless workflow as a way of building real-time games quickly. When working on experimental experiences such as Roguelike Celebration’s space, I think it’s essential to be able to spend your time focusing on hard questions surrounding what the most interesting experience to build is, rather than having to spend your limited engineering resources focused on hard scaling problems.

Scaling traditional real-time netcode is an incredibly difficult problem, even if it’s a relatively solved one. Our approach let us functionally sidestep a whole bunch of those difficult problems and focus on building a truly unique and magical virtual event, which absolutely resulted in a better experience for attendees than if we’d invested our time manually scaling.

Whether you’re literally trying to figure out how to scale your magical online experience, or you’re working on some other interesting experiment, I’d recommend taking the same approach as us: sidestepping difficult problems with outside-the-box design can let you focus your attention on more mission-critical design questions.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Roguelike Celebration space, you may want to check out the aforementioned design blog post or the code on GitHub.