Building An Open-Source Moves Clone: Day 1

One of my favorite iPhone apps is (or rather, was) Moves. Being able to see a daily breakdown of everywhere I’d been and all the walking and biking I did was incredibly useful for a whole bunch of reasons.

I recently uninstalled it from my phone. I always had vague concerns about sending that much data about my personal life to a third-party; the Facebook acquisition and subsequent changes to their privacy policy and terms of service were enough to get me to delete my account.

This week is reunion week at Hacker School, so I have some time to hack on an open-source project. I’ve decided to take on a rather ambitious goal: build a complete functioning Moves clone for iOS. The idea is a tool that lets users truly own their data; the app will not send any of your data to a third-party server unless you explicitly export it, and since it will be open-source there’s no worry of that ever changing.

In this initial stage, I’m defining “success” to mean having an iPhone app I can use to aggregate GPS and motion data in such a way that I can both get a useful visualization on my phone (a la Moves) and analyze the data myself with a JSON-based data export (much like the export provided by Reporter). I have a lot of bigger-picture ideas if the project is successful, but let’s take this one step at a time.

I’m not going to actually release the full source until it’s ready (it’ll eventually be on GitHub, license TBD), but I will hopefully be posting regular updates here with lots of code examples. Documenting the whole process, from dirty prototypes to finished app, will hopefully be a useful exercise for others.

Day 1: Playing With Data

Moves presumably features a lot of complex signal processing code that reads in raw accelerometer data to help figure out if you are walking, biking, or riding in an automotive.

The M7 motion coprocessor in the iPhone 5S does a lot of that work for you: Apple’s CoreMotion API exposes a high-level API that expresses something resembling that. Because my time is so constrained, my first order of business was to take a look at what sort of data CoreMotion and CoreLocation were returning me to see if it was accurate enough to use.

As Sandi Metz says, “you’ll never know less than you do right now”. My goal for the day was to write a lot of shitty throwaway code to experiment with what data I could get from Apple.

Persisting Data

Before receiving data from CoreLocation and CoreMotion, having a way to save data to disk seemed important. While I suspect the app will ultimately need the power of CoreData, it was definitely overkill for the requirements of a prototype, which are roughly “let me shove some data onto the disk and then retrieve it later”.

I created a very simple model class to contain both location and activity data, poorly naming it LocationList. I choose to use Mantle for now, purely to avoid needing to write NSCoding boilerplate.

@interface LocationList : MTLModel

@property (strong, nonatomic) NSArray *locations;

@property (strong, nonatomic) NSArray *activities;

+ (instancetype)loadFromDisk;

- (void)addLocations:(NSArray *)locations;

- (void)addActivities:(NSArray *)activities;

@endThis initial implementation is incredibly dumb. Calling addLocations: or addActivites: causes the appropriate internal array to be appended with new data, and then the object itself persisted to disk.

- (void)addLocations:(NSArray *)locations {

if (!self.locations) self.locations = [NSArray new];

self.locations = [self.locations arrayByAddingObjectsFromArray:locations];

[NSKeyedArchiver archiveRootObject:self toFile:self.class.filepath];

}fetchFromDisk merely retrieves that object again, or a new object if there isn’t one on-disk.

+ (instancetype)loadFromDisk {

return [NSKeyedUnarchiver unarchiveObjectWithFile:self.filepath] ?: [self new];

}(The class method filepath simply returns a handle to a filename based on the object’s class.)

To be clear: this is an absolutely terrible way of doing things. Even ignoring the eventual issues of memory requirements and complex querying with as large a dataset as I expect this app to have, there will almost certainly be nasty concurrency issues.

My goal wasn’t to write high-quality code that would last. My goal was to write the absolute dumbest thing possible that would let me see what the data I had coming in looked like. For now, this model provides a simple way to shove a small amount of data into a datastore and pull it out to display on-screen.

Processing GPS Data

Fetching location data, even in the background, is easy. After setting up a test app with the background location key set in the plist, I created a new class to help manage a CLLocationManager. It didn’t do a lot.

self.manager = [[CLLocationManager alloc] init];

self.manager.delegate = self;

[self.manager startUpdatingLocation];From there, the CLLocationManager will simply call its delegate method over and over again, even when the app isn’t running, with updated data. Given our persistence layer, all we need to do is keep pushing those new updates onto our list.

- (void)locationManager:(CLLocationManager *)manager didUpdateLocations:(NSArray *)locations {

dispatch_async(dispatch_get_global_queue(DISPATCH_QUEUE_PRIORITY_DEFAULT, 0), ^{

LocationList *list = [LocationList loadFromDisk];

[list addLocations:locations];

});

}To be clear, this is just as inefficient and dumb as our persistence layer. Specifically, this will eat up battery like there’s no tomorrow, and probably return a lot more data than is needed. While there’s a lot of low-hanging fruit to make this more efficient, I didn’t care. I can optimize for battery life once things are working; I wanted to see the full range of accuracy the GPS is capable of, and make that happen as quickly as possible.

The process for receiving and fetching motion events was essentially the same, except for not being able to get backgroud updates. Instead, when the app loads, I needed to query the device for any motion activity that took place while it was closed. That’s easy to do by asking for everything since the last event stored on disk.

Generating Test Data

Using the iOS simulator, it’s easy to falsify CoreLocation data. The simulator has a handful of pre-programmed routes you can select to simulate movement. However, that doesn’t exist for the M7. I ended up going for a brief walk and bike ride around the block to generate some data. Who says programming is a sedentary activity?

Visualization

The app’s sole view controller only has one view, a full-screen MKMapView. For the sake of visualizing the test data, I just used built-in MKAnnotation and MKPolyline objects.

The actual logic is a bit clunkier and longer than I’d like to show here, but it wasn’t particularly complex.

-

The location and activity arrays were first joined and sorted by timestamp, resulting in a complete chronological listing of all events.

-

All location events following a “stationary” motion event were considered to be places I stopped.

-

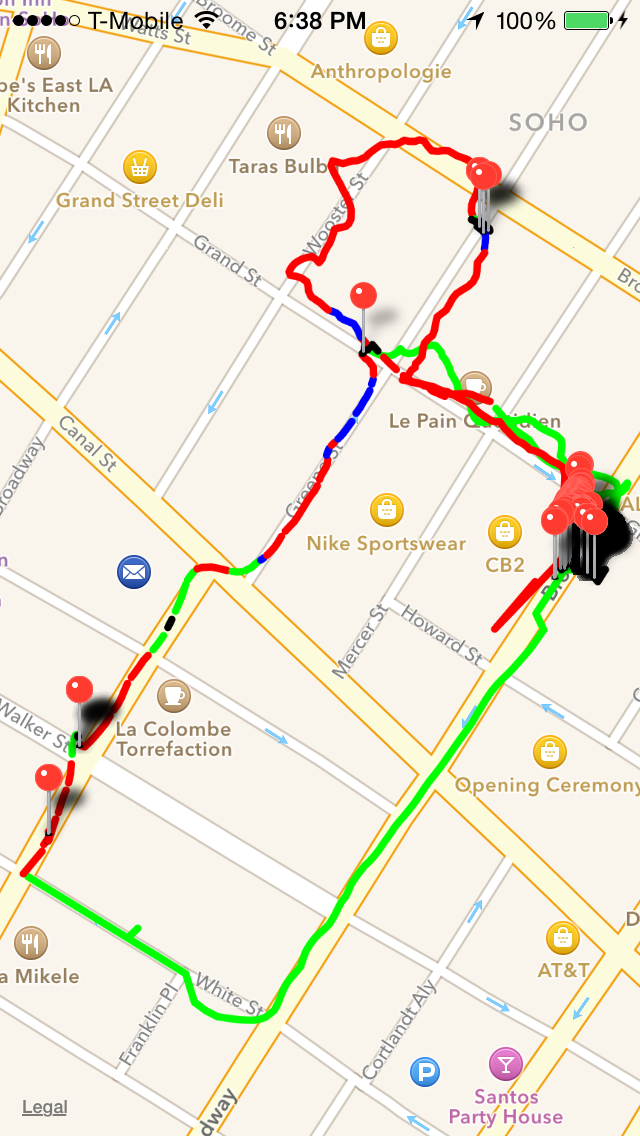

All location updates that took place between those stops were considered to be movement, respecting the movement types returned by CoreMotion (walking, running, automotive, unknown). These polylines were then rendered with different colors based on what activity type they were.

-

For the sake of argument, I arbitrarily said that all “unknown” movement with an average speed of above 1.2 meters per second (determined by averaging the

speedproperty of eachCLLocationobject in the path) was bike movement.

Here’s the result:

The data was fairly accurate. Basic data sanitization aside (smoothing out the lines, removing duplicate stops that are clearly the same location), there were two chief inaccuracies:

- The green line (representing biking) should be a closed loop, so some biking was misinterpreted as walking (red) and running (blue).

- The higher of the two stops in the bottom-left corner should not have been interpreted as a stop; it was a five-second pause while maneuvering between cars in traffic.

The largest problem is clearly going to be figuring out how to determine bicycle data, since the M7 doesn’t return that directly, but I’m fairly confident I’ll be able to find some sensible heuristics to improve that without needing to drop down to the level of processing raw accelerometer data. Even Moves doesn’t process bicycle data perfectly; I often found myself having to correct “walking” or “transit” paths into biking ones.

All in all, I think that’s pretty impressive for a first day of work. Above all, I proved my hypothesis: while the data isn’t perfect, it’s clear that the combination of GPS and M7 data should be more than sufficient to roughly approximate the work Moves was doing.

–

Update From The Future

Hello! If you’re reading this, you may be wondering what happened to this project.

Check out https://github.com/lazerwalker/Theseus. It (sort of) works, but is neither in great shape code-wise nor actively maintained. There’s some more info in the README.