Making Multiplayer iOS Games with Apple Multipeer Connectivity

After publishing my last blog post, I had a number of people ask me for details about the nuts and bolts. I said that Apple makes implementing local multiplayer easy: what exactly did I mean?

It seems relatively unknown, but Apple actually has an entire framework dedicated to enabling multipeer connectivity between iOS devices. First introduced in iOS 6 as part of GameKit, it was spun off into its own framework in iOS 7. How does it work? Let’s build a game and find out!

Since my goal here is to purely to show off how multipeer connectivity works, I’m just going to walk through the steps to adding networking to a game; this isn’t a tutorial in game development.

The full codebase for the game is available at https://github.com/lazerwalker/prisoners-dilemma. More specifically, all of the logic has been encapsulated in a single file for easier skimability. Were this production code you’d almost certainly want to encapsulate a lot of this behavior into more isolated and atomic units rather than shoving everything into a single monolithic view controller.

The game also uses ReactiveCocoa. Even if you aren’t familiar with ReactiveCocoa or FRP, I hope it’s a simple enough example that it’s still fairly self-explanatory.

Prisoner’s Dilemma

The game we’ll be using for our example is a two-player iterated prisoner’s dilemma game.

If you’re not familiar with the Prisoner’s Dilemma, the explanation of it is pretty straight forward. As per that Wikipedia link, the original formulation is presented as follows:

Two members of a criminal gang are arrested and imprisoned. Each prisoner is in solitary confinement with no means of speaking to or exchanging messages with the other. The police admit they don’t have enough evidence to convict the pair on the principal charge. They plan to sentence both to a year in prison on a lesser charge. Simultaneously, the police offer each prisoner a Faustian bargain. Each prisoner is given the opportunity either to betray the other, by testifying that the other committed the crime, or to cooperate with the other by remaining silent. Here’s how it goes:

- If A and B both betray the other, each of them serves 2 years in prison

- If A betrays B but B remains silent, A will be set free and B will serve 3 years in prison (and vice versa)

- If A and B both remain silent, both of them will only serve 1 year in prison (on the lesser charge)

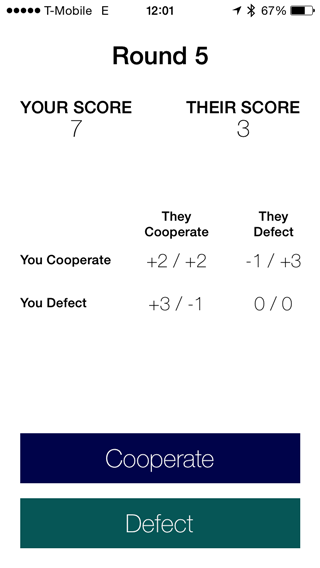

Here’s what our version of the game will look like:

Two players will each be given to options: to cooperate or to defect. You can see the payout matrix in the screenshot: if A cooperates and B defects, for example, A will lose 1 point and B will gain 3 points. Because we are making an iterated prisoner’s dilemma game, each player’s score accumulates over a number of rounds.

As an aside, if the idea of using game theory ideas like the prisoner’s dilemma within the framework of video game design is interesting to you, I highly recommend this talk, by Frank Lantz at the NYU Game Center, about the relationship between game theory and game design.

What needs to be done

At a high level, the game is pretty straight forward: each player chooses to either collaborate or defect on their own iPhone. After each player has chosen, the result is revealed, the score is updated, and a new round begins where each player selects anew.

We only need to do a few things:

- Keep track of what round we’re on

- Keep score for each player

- When a player has made a choice, communicate that choice to the other player’s device

Initial network connection

The obvious required first step to any sort of networked gameplay is networking two devices together.

The Multipeer Connectivity framework has a handful of objects that can help us with this.

A MCPeerID represents a single device that’s part of a session. It has a display name that’s used to identify it. In our example, we’ll just use the device name of the iPhone running the game.

An MCSession represents a single game session. At initialization, you give it an MCPeerID that represents your current system. As other devices connect, they will be added to the session object, which gives you a number of methods to send data to a given peer or set of peers. It optionally has support for encryption, and also has a delegate object for receiving incoming data from peers.

Setting up a connection requires an active session, which in turn needs a peer to represent the current system. This isn’t hard:

UIDevice *device = [UIDevice currentDevice];

MCPeerID *peer = [[MCPeerID alloc] initWithDisplayName:device.name];

MCSession *session = [[MCSession alloc] initWithPeer:peer];

session.delegate = self;For all this code, the object that manages these connections is also the session’s delegate.

Once a session exists, we want to actually add multiple devices to that session. For the sake of this demo, let’s display a UI on all devices, and let any device connect to any other one. To make that happen, we need to do two things: each device needs to advertise that it’s available to connect to, and then display a UI to connect to other nearby advertising devices.

The former is done through an MCAdvertiserAssistant object.

self.assistant = [[MCAdvertiserAssistant alloc] initWithServiceType:@"mlw-prisoner"

discoveryInfo:nil

session:session];

[self.assistant start];The serviceType parameter in the constructor is simply a string that uniquely identifies the networking protocol of your app. It’s the same format as a Bonjour service type. Beyond some limitations on length and allowed characters, it doesn’t particularly matter what it is, as long as it’s shared among all clients and unique from other services.

The discoveryInfo parameter is a dictionary that is passed along to other devices receiving the advertisement. There are various restrictions on what format the data can be in.

Finally, the session represents a MCSession object that sucessful peer connections will be added to. In this case, we’re using the MCSessionwe created in the previous example.

After calling start, the assistant will start broadcasting the device to all other devices within Bluetooth range or connected to the same WiFi network.

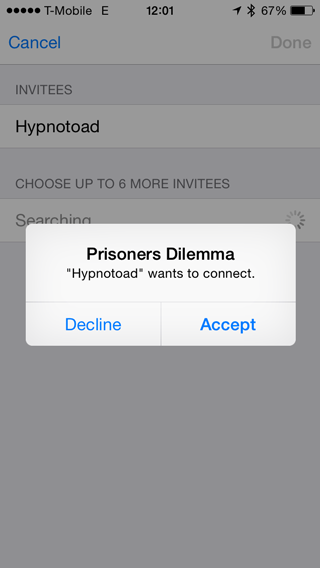

When another device tries to connect to a device that is advertising, an invitation UIAlertView will automatically be shown with the option to accept/reject it. If you want to build an alternate UI for that behavior, Apple provides a similar class, MCNearbyServiceAdvertiser, that provides all of this functionality except for the user-facing UI.

Browsing local peers

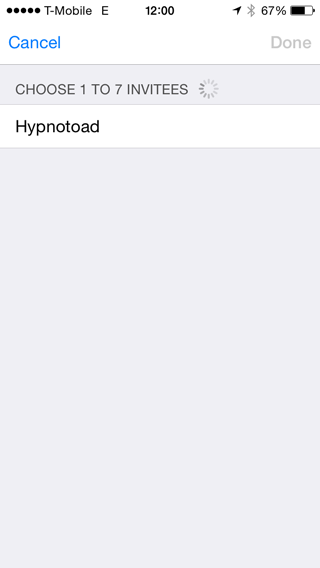

Now that each device is broadcasting itself, we need a way to browse available peers and attempt to connect to them. While it wouldn’t be hard to write this ourselves, Apple provides a prefabricated view controller that can handle this for us. Instantiating an MCBrowserViewController is easy:

MCBrowserViewController *browser = [[MCBrowserViewController alloc] initWithServiceType:@"mlw-prisoner"

session:session];

browser.delegate = self;

[self presentViewController:browser animated:YES completion:nil];The serviceType here needs to refer to the same serviceType our advertiser is broadcasting. Just like our advertising assistant, the passed in MCSession object is the session that will receive peer connections when they are successfully made.

In our case, the object containing all this code is a UIViewController, and the MCBrowserViewController is presented modally. After the user has connected to one other device, we want to dismiss the modal view automatically. This is done by making our view controller the delegate of the MCSession, and listening for when the session adds a new peer:

- (void)session:(MCSession *)session peer:(MCPeerID *)peerID didChangeState:(MCSessionState)state {

if (state == MCSessionStateConnected) {

[self dismissViewControllerAnimated:YES completion:nil];

}

}This logic would need to be a bit fancier if we were dealing with a game that had more than two peers, but for now we can safely make the assumption that a single successful connection means we’re off to the races.

(If you step through the full game code in a debugger, you’ll notice that when connecting to a peer this method is fired twice, first with an intermediate MCSessionStateConnecting state and then again with the MCSessionStateConnected state we’re looking for here.)

Additionally, we’ll want to dismiss the modal view controller when the user taps the ‘cancel’ button. We can do that by making our view controller the browser’s delegate.

- (void)browserViewControllerWasCancelled:(MCBrowserViewController *)browserViewController {

[self dismissViewControllerAnimated:YES completion:nil];

}Sending and Receiving Data

At this point, running the game will let two clients connect to each other, but not much else.

When making multiplayer games, concerns with how to let clients talk to each other exist at multiple levels. The Multipeer Connectivity framework deals with the low-level problem of letting two devices connect to each other and send data back and forth, and can optionally offer some assurance of message deliverability, but it doesn’t offer solutions to problems at a higher level than the transport layer. Once the two devices are connected, we still have to decide for ourselves what data to communicate and what format to serialize it in.

Let’s take a step back and think about what our data transmissions will actually look like. While we could find a way to serialize the entire game state and send it between the two devices, that’s not a solution that scales paricularly well to games more complex than this. Ultimately, at any given moment, our prisoner’s dilemma game only has a few pieces of state: how many rounds have been played, the current score, and which choice (if any) each player has made.

Each client should theoretically always know what round it is, what the current score is, and whether that client’s player has made a move yet, but it needs a way to know when the other client has made a move. Perhaps, then, each client should communicate with the other client only when its player makes a move, sending whether they chose to cooperate or defect.

In a more complex, production-ready game, we’d surely want more synchronization checks and failsafes to make sure that all of the clients’ game states stay exactly the same. In our case, we can add a little bit of safety by adding marginally more complexity: we’ll send the round number along whenever we send a player’s choice, so a client can ignore it if it isn’t for what it perceives to be the current round.

Since a player’s choice is binary (they’ve either defected or cooperated), we can represent both the round number and their choice with a single integer. The absolute value of the integer is the round number; whether the number is positive or negative indicates whether it represents a choice to collaborate or defect. The round number will be one-indexed rather than zero-index, both because this makes sense from a presentation standpoint and to avoid the trickiness of thinking about negative zero.

Again, a game that’s even marginally more complex will likely warrant a more complex data serialization scheme, but for the purposes of showing how the Multipeer Connectivity framework works it’s convenient to be able to condense each unit of data transfer down to a single integer.

Sending data

To send data to peers, MCSession has a few methods based on whether you want to send a raw chunk of data, a stream of data, or a resource via URL. In a real-time game you’d probably want to stream data to minimize overhead and lag. In this case, just sending bits of data as needed is simpler and perfectly sufficient:

typedef NS_ENUM(NSInteger, Choice) {

ChoiceNotMade = 0,

ChoiceCooperate,

ChoiceDefect

};

NSInteger round; // Represents the current round number

Choice yourChoice; // The player's choice

if (yourChoice == ChoiceDefect) {

round *= -1;

}

NSData *data = [NSData dataWithBytes:&round length:sizeof(round)];

NSError *error;

[session sendData:data

toPeers:session.connectedPeers

withMode:MCSessionSendDataReliable

error:&error];A positive round number represents a “cooperate” choice, whereas a negative number means “defect”. We serialize that integer into NSData, and tell the active MCSession object to send it to all connected peers, using the MCSessionSendDataReliable mode to ensure delivery of every bit of data.

The receiving end looks pretty similar, taking place in a delegate method on the MCSessionDelegate protocol.

- (void)session:(MCSession *)session didReceiveData:(NSData *)data fromPeer:(MCPeerID *)peerID {

NSInteger round;

[data getBytes:&round length:sizeof(round)];

if (ABS(round) != self.roundNumber) return;

Choice theirChoice = (round > 0 ? ChoiceCooperate : ChoiceDefect);

// ...

}And that’s all there is to it! There’s a small bit of other game logic — accepting user input and sending data to the peer as a result, calculating the score when a roud is over, etc — but that’s really all it takes to get the networked aspect of the game up and running. Again, the full source code, ready to run on your own iOS devices, is available on GitHub.

It’s worth reiterating (yet again) that this is WAY simpler than almost any real-world game you’d build using something like this. It’s only two players, so it doesn’t require negotation between multiple peers. It’s turn-based, so there isn’t any need to come up with a strategy for resolving incompatible actions that different clients send simultaneously. The information being sent between clients is trivially small, eliminating the need to worry about how to manage shuttling large amounts of data in a performant manner.

Again, these are all conceptual issues that any networked game will face. My main point here isn’t to tell you how to solve those. Rather, my hope is that I’ve shown how Apple’s frameworks can provide a nice tool to take care of the network transport layer for you, leaving you free to focus on coming up with a solution for those bigger-picture problems that works best for your specific game.